Abstract, geometric paintings

The writings and musings of author and artist Mike Rickett

Abstract, geometric paintings

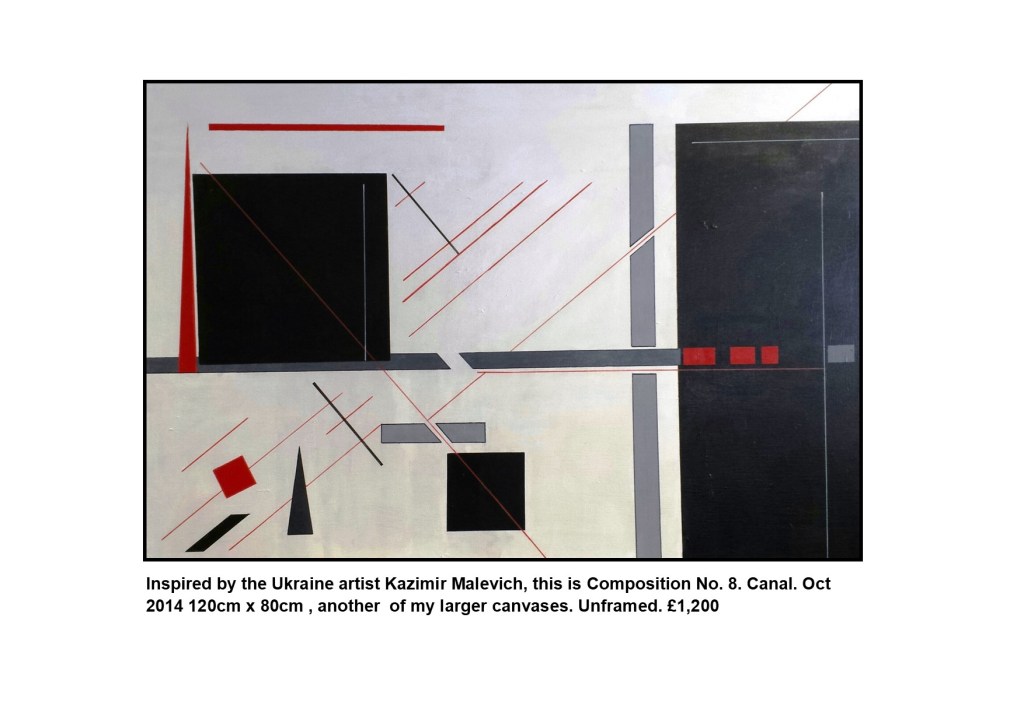

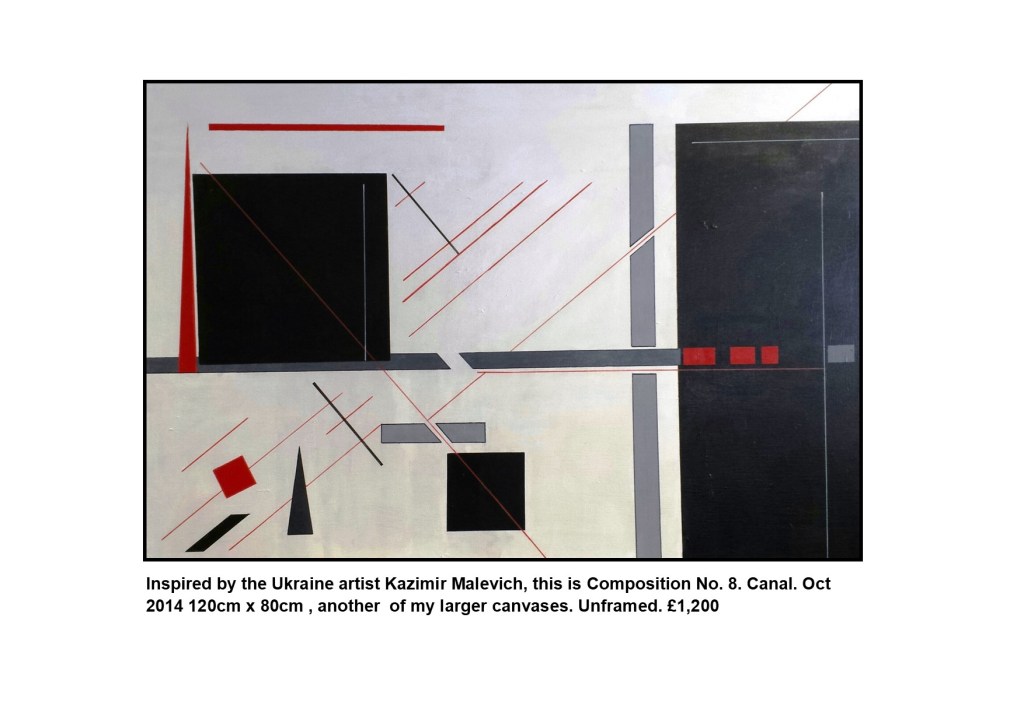

This is Composition No.12. measuring 81cm x 48cm. It is inspired by that great Ukranian artist Kazimir Malevitch.

He was an avant-garde artist and art theorist, whose pioneering work and writing had a profound influence on the development of abstract art in the 20th century. Born in Kiev to an ethnic Polish family, his concept of Suprematism sought to develop a form of expression that moved as far as possible from the world of natural forms (objectivity) and subject matter in order to access “the supremacy of pure feeling” and spirituality. Malevich is also considered to be part of the Ukrainian avant-garde (together with Alexander Archipenko, Sonia Delaunay, Aleksandra Ekster, and David Burliuk) that was shaped by Ukrainian-born artists who worked first in Ukraine and later over a geographical span between Europe and America.

Early on, Malevich worked in a variety of styles, quickly assimilating the movements of Impressionism, Symbolism and Fauvism, and after visiting Paris in 1912, Cubism. Gradually simplifying his style, he developed an approach with key works consisting of pure geometric forms and their relationships to one another, set against minimal grounds.

This painting is for sale. Sensible offers only please to mikerickett007@yahoo.co.uk. Buyers must be prepared to collect or arrange shipment.

A ghost story for Christmas

I haven’t, in truth, known Dr Irwin Jacobs for very long. I would stop short at calling him a friend because I don’t honestly believe he has anyone he could apply that title too. While appearing outwardly friendly, in reality, he struck me as a very self-contained person; a very private man who only very reluctantly reveals anything about himself.

I first met him in Llandudno in North Wales at a conference on The Study of Personality Disorder. It was organised by SANE, the mental health charity and was attended largely by medics and psychiatrists and others involved in the provision of mental health services. I was there as a freelance journalist with an interest in mental health, having written on many occasions about how destructive it can be to families and relationships.

I literally bumped into him at the hotel bar where he was sitting on a stool staring gloomily into a gin and tonic. I rather clumsily managed to spill his drink which he was about to sip. I naturally apologised profusely and immediately offered to buy him another, but he waved the offer away.

Dr Jacobs has a rather Teutonic face; startling blue eyes, a square jaw and a firm mouth that is not given to smiling. His thinning grey hair sits above a furrowed brow and a sallow face. We shook hands and I apologised again.

I sat on a stool next to him and introduced myself. I am Dominic Howard, quite well known in my chosen field by mental health professionals, even if I do say so with a degree of modesty! After we concluded the introductions, I asked him about his practice. He immediately became quite animated and went into some detail about the problems some of his patients present. It was, however, punctuated by nervous glances around the room, his eyes flickering from side-to side as though expecting a friend or colleague. I looked around but there were just other delegates standing in small groups in earnest discussion.

‘Are you expecting someone,’ I said, standing up, preparing to leave.

‘No, No,’ he said, placing a hand on my arm with a look that invited me to sit. I did so. ‘I thought I saw a cat,’ he muttered, almost under his breath.

I stared at him. ‘A cat?’ I repeated looking around the bar.

‘I’m allergic to them,’ he said by way of explanation, looking around furtively. For some reason I did not believe him but why would he lie about something like that? Our conversation then turned to topics to do with matters of the mind. It ended with us exchanging contact details. As a journalist I have always found it useful to collect people who are experts in their fields and for all his odd behaviour, Dr Jacobs did appear to be highly knowledgeable. We shook hands and parted.

That was a month ago and I have been busy writing a feature on stress at the workplace, a subject close to my heart, when I routinely look at my email queue and there is one from Dr Jacobs inviting me to call round for supper. To say that I am surprised would be an understatement.

I note that Dr Jacobs lives at Bedford Square, which is not that far from my apartment at Ridgemount Gardens, near the University of London. I reply saying that I would be happy to call round. I am curious, more than anything else, to see what life is like at Bedford Square. I note his address is not an apartment!

The door is opened by a man formally dressed. He asks me to identify myself and ushers me into a small but comfortable room to the left of the front door. I take it he must be a butler or manservant. I am astonished that they still exist in the 21st century.

Five minutes later he returns and invites me to follow him to a plush, but rather austere lounge. Jacobs is standing near an open coal fire. He steps forward and we shake hands. He treats me to a rather watery smile and waves me into an expansive easy chair. The Butler, who he addresses as James, is standing nearby awaiting instructions. Jacobs orders two whiskies.

I gaze around the room. It is slightly Edwardian; not quite Victorian but fussy in that everything obviously has its place. Along one wall are shelves full of tomes. I am always fascinated by bookshelves; what treasures are hidden away there, I wonder, and I am sorely tempted to explore, but I don’t. Instead, I look at Jacobs who is staring around the room furtively.

‘Do you hear anything?’ he asks softly.

I listen. There is just a heavy silence which is interrupted by James bringing our whiskies. I stare at him. His face could be made of stone. It is set and expressionless as he sets our drinks down on occasional tables.

‘I am informed by cook Sir, that dinner will be served in 30 minutes,’ he announces in a monotone. Jacobs nods in acknowledgement and James glides out of the room.

‘I didn’t hear anything,’ I inform Jacobs, ‘apart from the occasional car passing outside.’

‘You didn’t hear a laugh,’ he asks, looking at me closely. I shake my head, puzzled, and enquire why he asked.

He stares at a corner of the room. This is a strange house,’ he says. ‘Once the servants have left, I can’t help feeling that there are other people here. I can hear them. Mutterings and laughing, sometimes all night long. There is a cat too. I have no idea how it got in here but I see it every night, lurking in corners.’

I look around the room and then say breezily that there is no sign of any cats now and then ask him how long he has lived at Bedford Square.

‘It was bought by my grandfather,’ he says, relaxing a little. ‘We have lived here for three generations. Both my father and grandfather were medical men. I am the only one to practise psychiatry.’

‘Did you never marry,’ I ask a little hesitantly wondering if he might be offended by such a personal question.

He frowns and replies that he did but that his wife died suddenly just two years after they were wed. ‘It was toxic shock. She died in just two days of the bacteria taking hold,’ he says quietly. I have been alone ever since.’

Suddenly, James appears to announce that dinner is served so we follow him into another spacious room with a dining table in the middle with seats for ten people. There are two place settings at one end. The room is mostly lit by candles, two candelabra on the table and two meagre wall lamps which together manage to cast ominous silhouettes on the walls.

Dinner passes in a gloomy silence and it is with some relief that we eventually rise to leave the maid to clear away the dishes. We return to the lounge which is also poorly lit with just two small wall lights.

His patient involves a delusion that he can transform into an animal. It is often associated with turning into a wolf or werewolf; the name of the syndrome originates from the mythical condition of lycanthropy or shapeshifting into wolves.

‘The patient genuinely believes he can take the form of any particular animal and during delusional periods he can act like the animal.’

I decide to go online and see what a Google search reveals. The first is a news story in which police are appealing for information about Catharine Bancroft, aged 78, who vanished a year ago. I read the story. It seems she told a neighbour she was going to a local shop in south London and was never seen again. The neighbour is later quoted as saying she was devoted to her cat which had also disappeared. It was, apparently, a large black cat which she doted on. It was always with her. I stare at the photograph. There is no doubt about it. She is the spectral figure I saw standing behind Jacobs. And the cat I saw was no doubt hers too.

The second news story that comes up is five years earlier in the Daily Mail saying the actress Catherine Bancroft was retiring from the stage after a lifetime in the theatre. It seems she was a regular in West End productions. It goes on to list many of the shows she appeared in.

So why would she be haunting Jacobs, if indeed it was her I saw? And why did he say she committed suicide, if indeed it was Miss Bancroft he was referring to? The inescapable conclusion, given the documents I found, is that Jacobs was somehow involved in her disappearance but I find that difficult to believe. He may be a little odd but an eminent psychiatrist like him murdering and stealing from a patient is difficult to believe. Surely not. There must be another explanation.

But if she weren’t murdered, what could have happened to her? Suicide is simply out of the question. A well-known actress like her taking her own life would have been certain to have made the headlines.

I scroll through the other news items in which Catherine was mentioned but the headlines get smaller and the stories shorter as time goes on and there is no trace of her. There is only one story in which Jacobs is mentioned and that was when he revealed that she had been a patient of his for some time. No significance appears to have been attached to that.

I decide that I can do no more but I write up my research and file it away thinking that if Catherine does re-appear there will be story in it. I put Jacobs out of my mind and immerse myself in more pressing matters.

It is just a week later when I am sitting in a coffee shop sipping a cappuccino reading the Guardian when my mobile rings. I sigh and am minded to ignore it. I value my thinking time and interruptions are annoying. I glance at the screen which is saying ‘Dr Jacobs’. I really do not want to visit him again in that creepy house of his but I decide to answer and make an excuse, if indeed that is what he wants.

I click on it and listen but all I can hear is an odd subdued, whispered, muttering. I keep saying ‘Dr Jacobs, are you there’ but there is no answer, just the muttering and a strange, rather eery rustling sound.

Then, suddenly, there is scream which is so loud I almost fall off my chair. The two people sitting at the next table glance at me curiously as I hold the phone away from my ear. When I listen again there is just absolute, total, silence. Then I hear a sound that chills me to the bone; it is a sound I last heard in a butcher’s, the unmistakable sound of flesh being sliced. I rush outside and hail a cab, telling the driver to take me to Bedford Square.

I stand looking uncertainly at the door. What am I going to find behind it? Perhaps I should have rung the police first, but then if nothing gruesome has happened despite the scream, I would look foolish. For all I know Jacobs might have just been having a fit of hysterics. Having said that my instinct is telling me otherwise.

There is no movement in the windows; no lights are shining; they just stare down at me ominously. I press the bell and wait. There is no response. I press it again and notice that the door appears to be very slightly open. I push it gently and it swings open very slowly as though by an invisible hand, revealing the cavernous, dinghy hall.

I stare into its gloomy space. There is no movement, no sign of life. I suddenly have an almost overwhelming urge to walk away from this place but I know I must enter; something is compelling me to.

I walk slowly, fearfully, down the hall. I call out to Dr Jacobs several times; there is no answer, just an oppressive, brooding silence. I reach the lounge and stare at the door. I want to turn back; what will I find in there?

As I stand there transfixed, the door gradually opens of its own accord. I step hesitatingly into the room which is in partial darkness due to the curtains being slightly open. At first, I can see nothing in the gloom. I was expecting to see Jacobs in his armchair asleep but the two chairs are empty.

It is only then I notice the smell. It is a sickeningly dry, sweet metallic scent on the verge of being pungent and slightly suffocating, mixed with the odour of burning.

It is only when I walk past the first armchair that I see it. At first, my senses cannot interpret the scene that confronts me. I stare in open-mouthed horror at the carnage that lies before me. Bile rises up and I rush to a plant in the corner and throw up. I leave the room trembling, the scene etched into my mind.

Jacobs, or what is left of him, was lying in the hearth in front of the fire which had been lit and which was casting a red glow on the room.

Embers from the fire had somehow fallen on his chest and burned their way into him exposing a few ribs. He is lying in a pool of blood, but the most horrific sight is his face which has been shredded as if by a claw. One eyeball has been forced out of its socket and hanging down his cheek.

I stumble to the end of the hall into the kitchen and pour myself a tumbler of water. I sit on a chair until my breathing returns to normal and my heart stops its wild beating. Something is telling me to return to the room. I walk to the doorway and there, in the centre of the room, is an elderly woman. I know immediately it is Catherine Bancroft. She is staring at me, tears trickling down her cheeks. At her side is her cat, also staring at me, its eyes no longer glowing. She raises an arm and points to the floor and they both slowly disappear.

It is two weeks later that police discover a body in the cellar. It was quickly identified as that of Catherine Bancroft. I had some difficulty persuading them to search the cellar without revealing that it was Catherine herself who pointed it out. The half-burned documents I produced persuaded them that it was a possibility that Ms Bancroft had been murdered.

At the inquest, forensic scientists were unable to satisfactorily explain how Jacobs sustained such horrific injuries. An open verdict was recorded.

Just two days later, I found myself wide wake at 2.00am. I glance at the window. I always leave the curtains half drawn to let in light. The moon’s rays cast a sombre light on the opposite wall. I stare at the windowsill.

A cat is sitting there.

Copyright © 2025 Mike Rickett

All rights reserved.

1968

I last ran into Montague Stephens almost a year ago. We bumped into each other in London after a Mozart concert at St Martin-in-the Fields. I was idly standing around clutching a glass of mediocre wine afterwards when he sidled up alongside me. I introduced myself. He looked at me and murmured my name Michael Thorne thoughtfully, his head to one side. I spared him the torture of attempting to recall where he had heard or seen it and told him that I used to be a reporter which is where he no doubt saw my by-line. He nodded, obviously relieved and we enjoyed a really pleasant chat about the relative merits of Mozart and Faure, the latter being my favourite composer.

I was working in London at the time at a PR consultancy in Red Lion Street and he was a history lecturer at the London School of Economics. After the concert we would meet up occasionally for a few drinks and a chat, usually somewhere in Holborn which is where we both lived, until a new job beckoned, and I found myself once again back in Liverpool.

That was six months ago when I rented a really spacious apartment in an area which the newspapers termed ‘Leafy Allerton’ in that jocular way they have of attaching labels to everything.

It is, however, undeniably a ‘leafy’ area and just down the road, nestling in a crossroads, is a historic church built by the 19th century shipowner and merchant John Bibby. It was apparently built at the-then enormous cost of £25,000 as a memorial to his wife whose catafalque lies behind the altar.

I love buildings that have a ‘history’ and this one is a prize example, for quite apart from the founder’s reason for building it in 1872, the church is full of remarkable art in the form of fabulous Arts and Crafts stained glass windows, largely the work of Sir Edward Burne-Jones and Williiam Morris, the founder of the pre-Raphaelite movement.

Anyway, I started going there of a Sunday morning to enjoy Matins and the choir’s singing of the Venite and the Te Deum and Benedicite or the Benedictus or Jubilate Deo. I was a chorister myself as a boy, so I appreciate a good choir.

Anyway, last Sunday I was somewhat surprised to spot Montague in a side aisle before the service staring fixedly at a statue in the south transept. I had no idea he had left London, so I strolled up and gave him a dig in the ribs. ‘You sly dog,’ I said smiling. ‘Why didn’t you get in touch? I had no idea you were in Liverpool.’

He stares at me vacantly, his eyes glassy until he suddenly appears to realise I am there. ‘Sorry Michael,’ he mutters, ‘I was admiring that sculpture over there.’ He points at what looks like a marble group of figures. I walk over and read the caption, An Angel Carrying a Soul to Heaven. It was carved by the Italian artist Fabiani and is a replica of the one in Genoa.

It must have cost the founder Mr Bibby a small fortune.

‘Magnificent isn’t she?’ he breathes, standing next to me. ‘I can’t take my eyes off her. The church authorities apparently call her ‘Flossie,’ can you imagine that? Disgraceful and insulting,’ he declares indignantly, looking around hoping somebody was within earshot. Nobody is.

He moves a short distance away and summons me to join him. We have our backs to the statue, and he is pointing to a pew just two rows from the front and at the end next to the central aisle.

He lowers his voice to a whisper. ‘I was sitting there last Sunday morning,’ he says sibilantly. ‘The choir had just started singing the Te Deum, do you know it?’ I nod in the affirmative.

‘Well, as you know, when it gets to part where the angels sing God’s praises, I felt a kiss on my cheek. I jumped and looked around but there was nobody there.’

‘You must have imagined it,’ I say to him. ‘It might have been a gust of wind from the Bibby side door over there.’ I point to the door by the vestry.

He shakes his head vehemently. ‘I know what lips feel like. And it was definitely a kiss.’ He stares at me fixedly. ‘It was her,’ he says nodding in the direction of the statue.

I burst out laughing. ‘Don’t be silly Montague. The Angel is a marble statue. They don’t usually suddenly come to life and start kissing people.’

‘I know what I felt,’ he says abruptly and marches off to the door. I turn and stare at ‘Flossie.’ She is certainly beautiful but definitely immovable. I shrug, thinking that poor Montague must be losing it.

It is almost a month later when I next see him. It is a Saturday, mid-December and I am on bustling Allerton Road, full of people with their eyes firmly focussed on the last few shopping days before Christmas. I had just been to the fishmongers for my weekly treat of Manx kippers when I spot him trudging along outside, his head bowed, the very picture of melancholy.

I catch up with him. ‘Montague,’ I call. He stops and turns, and I am disturbed at the change in him. His face is a pasty white and there are yellowish bags under his eyes.

I suggest we go for a coffee. He reluctantly agrees. When we are seated I stare at him. ‘What on Earth has happened to you? You look dreadful. Are you ill?

He smiles grimly. ‘I suppose you could say that.’ He takes a long gulp at his coffee and studies the people around us, muttering: ‘She will be here somewhere. You can’t always tell but she will be watching me. She always is.’

I look around. The café is quite full; there are people in ones and twos, all doing something; chatting, reading, or simply looking at the passing scene outside.

‘Nobody is taking the slightest bit of notice of us,’ I say, hoping to reassure him. Who do you think is watching you; who is she?’

He glares at me. ‘Who do you think? That bloody statue.’ He sighs and slumps in his chair. ‘That first night after I studied her in church. I woke at midnight. I felt something was wrong. I sat up in my bed. I always have the curtains and window slightly open. It was a full moon and there was a shaft of light shining in my room and there in the corner there she was, staring at me. There was something about her eyes. She wanted me to look at her, but I knew that if I did I would be lost. Then she began getting closer, her wings outstretched. I was terrified. I ran out of the flat on to the street in my pyjamas. One or two people walked past even at that time and stared at me curiously.’ His brow is furrowed as he gives me a pleading look.

‘You know, I think she wants me to join her,’ he whispers.

I am about to make a joke of it by saying she might be doing him a favour by taking him to Heaven, but I don’t. Instead, I say gently: ‘Are you sure you aren’t imagining all this? You might have been overdoing things at the faculty lately. I know there’s a lot of pressure to get Firsts these days. Maybe you should get medical help. Go and see your GP. I’m sure they will suggest something,’ I end a little vaguely.

He reaches into an inside pocket and produces a large, pure white feather. He places it on the table. ‘That was on the floor in the morning,’ he says. ‘Do you still think I imagined it?

I am lost for words. I stare at it. ‘Monty, I assume you mean Flossie by She, don’t you?’

‘Don’t call her that,’ he snaps. ‘She doesn’t like it.’

I frown. ‘Whatever you want to call her, she is a marble sculpture.

Nothing more. She can’t suddenly come to life. It is just impossible.’ I pick up the feather and hold it up. ‘And this could quite simply have blown in through the window. It looks like a seagull feather to me.’

He snatches it back and scowls, backing away. ‘You don’t believe me, do you, but you will, just wait and see.’ And with that he slinks off.

I am in a quandary. I am worried about him. I find his story difficult to believe and the following Sunday morning I stare at the statue. It is, without a doubt a beautiful piece of work. I wonder why they called her ‘Flossie.’ It seems completely incongruous for something so beautiful. As I stare, her face turns towards me, and she smiles.

I shake my head. I must have been dreaming. I look again and she is unchanged, her finger pointing to Heaven for the departing soul.

After the service I seek out the vicar, the Rev Maurice Bartlett. We are good friends. He was appointed two years ago and we hit it off almost immediately. He prepared me for Confirmation as well as marrying me to the wife I later divorced. He is an intelligent and likeable man, and as a former Guards officer, is well versed in the ways of the world.

We both enjoyed a lively debate, and I would rather impudently introduce topics like ‘What is God?’ usually accompanied by a whisky or two.

Anyway, I decide to ask if we could have a chat and later, in the early evening, I call around to the vicarage.

Once we have dispensed with the preliminaries, I tell him about Montague and his fantasy which is what I have decided to call it.

After I have finished he is silent for a while. Finally, he frowns. ‘He isn’t the only one to think there is something about ‘Flossie.’ One or two people have said they have had disturbing dreams about her, to the point in one or two cases, where they have even stopped coming.’

I am astonished and ask him if he is serious because Maurice can sometimes be a bit of leg-puller. He assures me he is.

‘There is something else too,’ he continues. One or two people who have been in the church of a night when just one or two lights are on, and they say they have felt a presence there and usually leave as soon as they can.’

‘Have you ever felt that?’ I ask. ‘You must have been there many times on your own.’ He grimaces and says he honestly hasn’t. ‘Maybe the presence is scared of me,’ he says grinning.

‘Maybe it’s Fanny Bibby getting out of her catafalque,’ I respond. ‘Perhaps she and Flossie get together for a bit of a chinwag when nobody is around. We both laugh at that thought.

He is looking thoughtful. ‘There is something else too that has been reported to me. A strange light has sometimes been seen in the North Chancel window. No other light have been on in the church, just in that window.’

He studies me. ‘You probably don’t understand the significance of that. That window was installed by Burne Jones in 1881. It depicts angels and is a memorial to John Bibby’s children.’

He looks at me questioningly. ‘Angels again you see. If you are looking for a reason, maybe that’s it.’

‘So, it comes back to “Flossie again.’” I say. He nods.

I sigh. ‘So, you are saying that it is distinctly possible that Montague isn’t imagining all this. Is that right?’

‘Oh well, I wouldn’t go that far,’ he says hurriedly. ‘It is entirely possible he has some kind of mental disorder which has magnified the stories about ‘Flossie’ he may have heard. He really needs to see a doctor.’

It is exactly the same conclusion I had come to, and I told him so. I stare at him quizzingly. ‘Do you actually believe all the stuff you’ve told me?

‘Let me refer you to the Bible,’ he says. ‘In my Father’s house are many mansions: if it were not so, I would have told you. I go to prepare a place for you. And if I go and prepare a place for you, I will come again and receive you unto myself; that where I am, there ye may be also. And whither I go ye know, and the way ye know.’

‘Is that a “yes” or a “no”?’ I ask.

‘I’ll let you decide,’ is his response.

On my way back to my flat, my thoughts return to that odd dream, if that’s what it was, I had in the church. It can only have lasted for perhaps a few seconds and then the statue was back to normal. I shiver.

Back in my flat I notice there is a message on my phone machine. It is from Montague. He sounds agitated. I press callback but it just rings out. I decide to go around and find out what the problem is and why he isn’t answering his phone.

When I get there he is sitting on his step, his head in his hands. ‘She won’t leave me alone,’ is all he says pleadingly, nodding inside. I assume he means ‘Flossie.’

‘What do you mean? I ask.

‘She is in my room all night. I am too scared to close my eyes. I don’t think I would wake up.’ I shake my head and sigh. I tell him I will go and look around. I’m not sure what I expect to find.

There is nothing unusual in any of the rooms. I join him on the step and tell him that everything is entirely normal and then an idea comes to me. ‘Why don’t you go away for a few days; a week perhaps? Do you have anyone you could stay with for a while? You don’t have to tell them exactly why; just tell them that you urgently need a break.’

‘There’s my sister Polly in London,’ he says slowly. I tell him to ring her straight away and if she agrees I will run him to the station. He disappears inside and returns. He asks me to go with him while he packs a bag. I takes him just ten minutes.

I drop him off at Lime Street Station. His demeanour has completely changed. He was smiling broadly when he climbs out of the car, and I congratulate myself on a problem well solved.

The following Sunday I go to church. It is Matins as usual but this week with the addition of the Eucharist following. While the choir are singing I stare wonderingly at the statue. I was about halfway down the Nave but even at this distance I can tell there is that indefinable something about her. I know this sounds insane, but I can almost feel her studying me.

At the end of the service, I seek out Maurice and update him on Montague. He agrees that it was exactly the right course of action.

That night I watch the BBC’s excellent annual ghost offerings. It is always one of M R James’ s creepy ghost stories. This year it is The Stalls of Barchester. A scholar, Dr Black is engaged in cataloguing the collection of the library of Barchester Cathedral. He is finding the work heavy going. However, the librarian and Dr Black begin reading the diary of Dr Haynes, an ambitious cleric who finds his promotion to Archdeacon blocked by a geriatric incumbent. The impatient Haynes, played by Robert Hardy, conspires to hasten the Archdeacon’s death and is duly appointed Archdeacon. However, his diary reveals that once in post Haynes becomes increasingly disturbed and is plagued by unnerving events, including a phantom cat, and carvings coming alive in the cathedral stalls.

I’m not sure whether it was that or ‘Flossie’s’ alleged hauntings, but my night was extremely disturbed. I awoke at 2.00am, or I thought I did but I can’t be sure. I may have been dreaming. It was a sound in my room I think, a strange rustling. I glanced at my window which I always leave slightly open, thinking that perhaps a bird may be in the gutters. But the sound wasn’t coming from there; it appeared to be nearer the door.

My room is never completely dark, even though my curtains are drawn. A lamppost outside casts an orange glow which permeates through my curtains. The orange glow is brightest on the door, almost opposite my bed. As I stare at it, I can see the door handle slowly moving. I gaze in horror as it stops, and the door gradually begins to

open. ‘Who’s there?’ I shout. I follow it up with ‘I’m ringing the police.’ I stand by the side of my bed.

The door is open wide now. Beyond is the hall in a blackness but as I stare, I can see a shape or shapes which are moving or writhing. I scream and fall onto the bed.

The sun is shining through my curtains. I am lying on my bed. Why am I on the bed and not in it? And then I remember the nightmare. Was it a nightmare? I’m not sure. It is all a bit fuzzy. I recall it had something to do with the door. I glance at it, but it is firmly shut.

I have a feeling of unease or dread, and I don’t know why. I search every room in the flat. I’m not sure what I expect to find but everything is as it should be.

I go to work which is taken up with the demands of a client in the form of the Plessey company on Edge Lane. The nightmare fades as nightmares so often do and the following nights are undisturbed which convinces me that it was all in my imagination.

The following Friday there is a message on my phone informing me that Montague is back home in his flat after a ‘really enjoyable week’ and would I fancy a pint or two a little later? I ring him later and we agree to meet up in the Rose of Mossley pub on Rose Lane.

I almost fail to recognise him when I spot him leaning on the bar. He is all smiles, transformed from the introspective, gloomy man who had set off to London. ‘You know, I think you may have been right,’ he informs me when we are sitting down. ‘I really do think it may have all been in my mind.’ I have to stop myself telling him about the ‘incident’ in church when I imagined ‘Flossie’ smiling at me.

He tells me he is moving back to college in London next week and I am welcome to visit whenever I want. I thank him.

As we part I ask him if he is likely to be paying All Hallows a final visit on Sunday. He stops and he stares at me strangely, an odd expression I cannot quite define before saying quietly: ‘I think not.’ And with that we part.

The following Monday my phone rings as I am about to go to work when my doorbell rings. Outside are two men who stare at me grimly.

‘Mr Thorne?’ It’s more of statement than a question. He produces a warrant card and introduces himself as Inspector Dean and his colleague as sergeant Finney. He asks if they could come in ‘for a chat concerning Mr Montague Stephens.’ I lead them into the kitchen and look at them expectantly.

‘We understand you are a friend of Mr Stephens,’ the inspector says. I nod. ‘When did you last see him?’ he then asks.

I briefly recount our conversation the previous Friday and tell them that he was intending to return to his college today. I raise an eyebrow expectantly and ask if anything is wrong.

They exchange glances. ‘I’m afraid we have some rather bad news,’ says the inspector. ‘Mr Stephens was found dead earlier this morning.’

I am stunned. ‘He was fine on Friday and in perfect health. What happened?’

‘We aren’t sure. As yet we haven’t been able to establish a cause of death. There is no sign of a disturbance despite a neighbour hearing shouting and a cry for help which is why he contacted us.

The pathologist was unable to throw any light at the scene. We will know more after a postmortem. Our immediate task is to notify next of kin. Would you be able to help with that?’

I tell him that he had just returned from visiting his sister in London and that the London School of Economics would undoubtedly have details. He nods and they turn to go. As they are about to walk out, he turns: ‘There was just one thing. He had a very odd expression on his face; both his eyes and his mouth where wide open as though something had deeply shocked him. I’ve never seen anything quite like it.’ He shakes his head mournfully and they leave.

It was a few days later that I learned that the postmortem decided he died from cardiac Arrhythmia or seizure, but they were unable to say what caused it.

I am disturbed. What could have happened to him? Inevitably, my thoughts turn to ‘Flossie.’ Could she have had something to do with it? And just as speedily, I dismiss it. That is just too ridiculous for words. It was probably a heart attack. I know of people who have literally dropped dead on the spot because of that. What is the betting that is what the PM will find. All the same, I feel unsettled for the rest of the day and decide to call on Maurice at the vicarage later.

He agrees with my diagnosis when I outline what the police have told me. ‘He was obviously a very disturbed man,’ he says quietly. ‘I shall pray for him.’ He then treats me to a calculating look. ‘You mustn’t let all this get to you. You did what you could to help him. You have nothing to reproach yourself for.’

The following day, a Saturday, is spent in Liverpool’s Central Library researching the science behind wire-free communications for the Plessey company, something that promises to revolutionise life in the future.

That evening is very disturbed again. I can’t relax and I have no idea why. I have the feeling I am not alone which is crazy but all the same I keep imagining I see movement out of the corner of my eye but when I turn to look there is nothing there. Am I imagining it? All this business with Montague has really unsettled me. I decide on an early night. Perhaps things will feel better in the morning.

I awake suddenly. I’m not sure why; was it a noise or something else? I’m not sure. I do know it is very cold and a shaft of moonlight shines coldly through the gap in my curtains lighting up something moving on the opposite wall. I sit up and stare. At first it looks like an image of something grotesque, a writhing mass of flesh which gradually coalesces into a pair of eyes which protrude from the wall and are slowly surrounded by a pair of wings and then an upper female body.

The eyes bore into me and the entire apparition begins to slowly move towards me until it reaches the end of my bed. I shrink back and try to scream but I can’t because my throat is so constricted all that emerges is a dry croak. I lurch sideways and fall onto the floor, banging my head on something hard.

I awake on the floor. I am cold, very cold. Daylight is streaming through the window. What am I doing on the floor? I am trembling and stand, reaching for my dressing gown. It is then I remember the nightmare. I must have fallen on the floor when I was writhing in bed.

But was it really a nightmare?

It must have been. I stare at the wall. All nightmares are vivid at first and then become a little fuzzy. I close my eyes, and I can still see the apparition. It didn’t feel like a nightmare. It was just so real. I shudder.

I decide to go to church after breakfast. The walk will do me good anyway and, hopefully, the uneasy feeling that has descended on me will dissipate.

I choose a pew on the opposite side of the church from ‘Flossie,’ and I am also behind a pillar so that I do not have line of sight of her. I’m not sure why. I just feel I want to distance myself from the statue. I am also at the end of the pew next to a side aisle.

The uneasy feeling has failed to dissipate; if anything, it becomes stronger as the service proceeds.

The choir start singing the Te Deum and as they sing: ‘To thee all Angels cry aloud: the Heavens, and all the Powers therein. To thee Cherubin and Seraphin: continually do cry.’

I am staring at the pew in front of me and suddenly fingers begin slowly crawling their way over the top. At first I assume there must be a child sitting there, but there is nobody there. I stare at them in horror; they are a deathly white, slightly green as though rotting.

It is then I feel a kiss on my cheek . . .

About the author

Mike Rickett is a member of All Hallows Choir. He is an artist and a writer. He was previously a daily newspaper journalist and at one time was head of public relations for National Girobank and PR Executive for the Plessey Company.

The first of the ghost stories

February can be an odd month these days; odd in the sense that you never quite know what to expect as far as the weather is concerned. Take today, for example. It is the middle of the month and yet the sun is shining brightly, and it should have felt warm outside but there is a cold, merciless wind blowing from the north and everyone is wrapped up in their fur-lined coats

Yesterday by contrast, threatening clouds loomed overhead which in past years would have almost certainly been a portend of snow but there was nothing but cold rain that seeped through to your bones. When I was a little girl, I would have been certain to be building a snowman with my dad this time of year. Maybe there is something to all the climate change furore after all.

I am Naomi Richards and I am an artist and psychic but before you snigger or move on to something else, I should say in my own defence that I tend to play down my psychic abilities because people are inclined to think I am either slightly bonkers or a charlatan. And I assure you I am neither.

Also, art is something I have toyed with all my life in an amateur way; something I did almost as a means of self-expression; a way of formalising my feelings about people and life in general, especially during the uncertainties of my teenage years. It was only after my painful divorce that I decided to take it seriously by spending six years in university winding up with a Masters.

I sell a canvas now and then and people appear to like my work but, sadly, not enough to pay the bills for my apartment on Liverpool’s Rodney Street, a fashionable address in consultant land in the city centre with the majestic Anglican cathedral just down the road. Not that I am on the expensive ground floor you understand. No, I reside on the first floor which is two flights up but that’s OK. It’s still a good address from which to run my other business which is my psychic consultancy. Sounds rather posh and pretentious, doesn’t it? But I assure you it isn’t. I just help people if I can; people who are bereaved or in pain or who are lonely or troubled.

You may be tempted to think that I am eerie old lady with a moustache, wearing a pointy hat with a broomstick in the corner and, of course, the mandatory black cat. But I have none of those, not even the cat and especially not the moustache. I am actually in my late twenties (28 if you really must know) with light brown hair combed back in a bushy ponytail that hangs half-way down my back. People have been known to remark on my eyes having a magnetic quality. I wouldn’t know about that. I just know they are grey. I’m not a large lady either, nor am I skinny. I think I have a pretty good figure actually; not one you would perhaps associate with the dark arts. (Whatever they are!).

I find it difficult to explain my psychic abilities to people because it is something I have lived with all my life. When I was little, I was terrified by the voices I heard and the things and images I saw. At first, I thought it was something that happened to everyone but then when I told my mum what I was seeing or hearing she would stare at me warily with a very worried look on her face. She dragged me off to our GP and then to a variety of consultants who all declared that they could find nothing wrong with me. It was then I realised that it was just me seeing and hearing things. After that, I learned to keep my mouth shut.

As I grew older though I began to realise that I should not be frightened and that I could use my abilities. I knew instantly who I could trust and who I could not, for example. I knew my husband was cheating on me long before I dragged it out of him. And I very often know when something is about to happen. They happen as images in my mind – I call them flashes – which last for perhaps a second or two – and then they are gone. It would then be a day or two later that the event or events would happen. These days I am sometimes called in by the local Police when a person, especially a child, goes missing and sometimes I can help locate them and sometimes I can’t.

Anyway, I am gazing out of the window of a south Liverpool pub watching all the activity as shoppers hurry past in the cold February sunshine with heavy bags from the nearby shopping centre. I am sitting at my usual table by a window with the sunshine casting a golden glow on the table in front of me. It is one of the monthly psychic sessions I do here, and I have a full list as usual. Most of them will be my ‘regulars’, mostly elderly ladies but by no means exclusively so. I do get men too wanting to know how what their careers have in store for them and girls wanting an insight into the latest or prospective boyfriend. It’s a mixed bag and it greatly helps to pay the rent!

The sessions are organised by Sid Driscoll, a man with a colourful background which a bent nose and a cauliflower ear testify to. He is not a man to get on the wrong side of but he’s an asset at these sessions in that he is more than able to deal with any troublemakers. I call him Sid the Fixer! Not that it is a potential problem here, but it can be when we hold sessions in the city centre when drunks come in ‘for a lark’.

My first customer is Betty, an 85-year-old regular who lost her husband almost 20 years ago. I think she is basically lonely and comes in for a chat apart from getting in touch with her husband. It always brings tears to her eyes and Sid invariably brings her a cup of tea when I give him the nod. He will chat to her and by the time she leaves she will be laughing.

The rest of the evening goes smoothly as it usually does until an unexpected client suddenly appears in front of me. I am reading a few notes and am about to pack up when I look up and there she is. I look at my list and I have seen everyone on it. Sid must have taken on a latecomer without telling me. I shake my head a little impatiently and look at the woman who is gazing at me in an odd way, almost as though she is looking through me with eyes that do not blink. I can feel a shiver along my spine. She is probably in her 50s with iron grey hair, a deeply lined face and a threadbare brown coat. I clear my throat rather noisily and ask how I can help her. She doesn’t reply but instead lifts an ancient handbag and pulls out a cutting on a yellowed paper. She slides it across the table to me and I stare at the headline which says. Housewife vanishes. And then, underneath Mother of two goes for a walk and is never seen again.

I am about to read the story underneath but instead I look up intending to ask why she has brought it to me but there is nobody there. I look around at the other tables, but they have all packed up and left. There is just me and Sid, sitting on a stool at the far end of the bar, enjoying a pint. I put the cutting in my bag and walk over to him. ‘Fancy a pint,’ he says, grinning, displaying a row of uneven teeth.

‘No thanks Sid. Some other time. ‘Who was the latecomer you sent over without telling me,’ I say, a little annoyed.

His brow furrows and he stares at me as if I’m mad. ‘Eh! I didn’t send anyone over luv. I would have asked you first, you know that.’

‘Well, a middle-aged woman appeared at my table, didn’t say a word, just handed me a cutting and then disappeared.’

He shrugs. ‘I didn’t see anyone. Last I looked at your table you were on your own, reading something by the looks of it. I wouldn’t worry about it. Sure, you don’t want a drink?’ I shake my head and sigh. ‘Thanks anyway Sid. I’m tired. See you soon.’

I walk down the road to the bus stop and within minutes I am on my way to Rodney Street. I slowly start to climb the two flights of steps at number 18 but as I do, I can hear steps on the stairs behind me. I stop and look down the stairs but there is nobody there. I must have imagined it. I carry on up and open my door and switch the lights on. My first action is to put the heating on. It is freezing outside and not much warmer in here. I leave my coat on until it warms up a little. I make a coffee and settle into my favourite chair and switch the TV news on.

I feel unsettled and I don’t know why. I look around the room, but it looks the same although is it my imagination or does the corner opposite the windows look darker than usual? Is that a rustling sound I can hear? I shake my head and decide it is all in my imagination and then I remember the cutting the strange lady gave me. I dig around in my bag and look at it under the lamp alongside my chair. The paper is yellowed so it is obviously at least five years old I would say. Maybe even older. I read the story. It seems the missing woman’s name was Nancy Derebohn and her husband is quoted as saying she left the house one night saying she was going to visit her sister a few streets away, but she never arrived. A search of the neighbourhood revealed nothing.

I decide to Google her name to see what comes up and I discover that Mrs Derebohn vanished fifteen years ago which explains the age of the cutting. There were no sightings of her and while the Police suspected foul play no body was ever found. Later reports said that her husband Roy was questioned but released. It seems she is still officially a missing person. It is then I come across the picture of Mrs Derebohn. It is the lady who came to see me. No doubt about it. Was she a spirit? Although spirits hold no fear for me, I am feeling slightly uneasy. I shiver.

It is late so I decide to turn in. I walk over to the windows and gaze down at Rodney Street. The old-fashioned gas lamps, now electric, bathe late night pub and club goers in pools of frosty light. Very soon, even Rodney Street will be still and silent. I draw the blinds and head for my bedroom where I partially draw the curtains. I have never really liked a totally dark bedroom and I like the shafts of light from the streetlamps below. It stems from when I was a little girl when I was constantly afraid of what I might see in the dark.

I take a hot water bottle to bed with me and soon its warmth has suffused its heat under my duvet, and I snuggle down and lull myself to sleep thinking about my latest canvas.

It must be 2am when I awake with a start. I sit up in bed rubbing my eyes. Was it a noise or something else that woke me? The shafts of light are shining through my window and it is quiet – too quiet. Silence can come in many forms I find – it can be menacing, suffocating or it can be welcoming or comforting but this silence is different. It has an expectancy about it. All my instincts tell me that something is about to happen. I look around my room. It is then that my eyes are drawn to a dark corner by the door where there is an even deeper darkness, beyond the shafts of light from the street lamps.

There is something there; it begins to coalesce into a vague amorphous shape; transparent and very slightly glowing. As I watch, it gradually takes shape and glides slowly towards me until it reaches the foot of my bed. It is the lady who appeared at the readings yesterday; Nancy Derebohn. Once again, her eyes bore into me. I ask her softly what she wants of me and then, after the silence continues, how I can help her. By way of an answer, in my mind I see a street; a row of terraced houses and then a front door, No 92. I know she wants me to go there. I am about to ask her why when a feeling of terror and desolation hits me like a wave, and I hear a howl of anguish. It is so strong I gasp and close my eyes. Something terrible happened to her. I know it. I can feel it. I open my eyes and she has gone. I decide to get up and make a cup of tea. I cannot sleep after that experience.

I cradle the hot cup in my hands and search for the cutting that Nancy gave me. I know the number of her house and I know it is in Liverpool, but I don’t know which street. I look at the cutting again and eventually I find it – Freshfield Road. I find it on Google maps and discover it is not far from the pub I give readings in. I shall pay it a visit tomorrow.

As it happens the following day is bright and sunny and I am busy with things artistic, which includes looking at a studio I am considering renting, so by the time I get back to Rodney Street it is early evening and the shadows are getting ominously longer on the buildings opposite.

I have a hurried egg and chips with a couple of slices of ham with a large mug of tea. I really don’t care if it isn’t trendy. It’s filling and its cheap and that’s all that matters. I get the bus at the bottom of my road and head for south Liverpool. By the time I am walking past the pub on my way to Freshfield Road it is getting dark and the street lights are beginning to switch on.

I reach number 92 and it looks very dilapidated, dirty windows, peeling paint and a general uncared-for appearance. I wonder if, in fact, anybody lives there and how I explain my presence if anybody does come to the door. I really can’t say that I saw a ghost last night who told me to come here because I’m sure the door would be very swiftly slammed in my face. I decide I will simply ask for Mrs Derebohn and see what response I get. I have just realised there is something strange about the street. There is no sign of life. There are no lights and no cars either. All very odd.

I climb a couple of steps and look for a bell. There isn’t one so I knock. I can hear the sound echoing around inside. I wait but there is no response. I decide to knock once more and to leave if there is still no response.

I knock again, louder this time, and just as I am about to bang the door again, it opens slightly. I stare at it and push it open revealing a blackness. I call asking if anyone is there but there is just a stony silence. I look up and down the street, but it is empty. The lights glimmer dimly, and it is now getting dark. I stare at the stygian blackness in what I suppose is the hall. I can feel the hair at the back of my neck rising. I don’t want to enter but I also know I must. I leave the front door wide open to give at least a little light. I tread warily into the hall, feeling my way. The silence is absolute and oppressive. There is a doorway on my right which I decide to ignore and then, in front me is the stairs. To the right is another door which I push open and gingerly tread my way into what I assume is the sitting room. Something brushes my face and I put my hand to my mouth to stop myself screaming.

A little light from the window shines grimly into the room. I can hear a voice, a man’s voice, faint but growing louder. Then, suddenly standing in front of me, is a tall, gaunt, heavy-set, unshaven man, his teeth bared. He is calling me a slut, a whore, he raises his hand and I flinch as it passes through me. His face is contorted in fury, flecks of white at the corners of his mouth. He bends down towards the fireplace and is now holding a poker which he brings down on my head, once, twice, three times. I look down at the floor and there is a body of a woman, her face looking up at me. It is Nancy. Now I know why she wanted me to come here.

I run out of the house, tears streaming down my cheeks. I run up the road until I reach the end and suddenly there are lights, traffic, people walking; people talking; people laughing. I stop and lean against a wall and bury my face in my hands.

‘Are you alright luv,’ says a kindly lady who stops, a concerned look on her face. I nod, smile wanly and assure her that I am and that I will be fine in just a minute or two. She looks uncertain and walks on.

As I walk, I begin to wonder if all that was a dream. The house and indeed the entire street for that matter. I doubt very much whether either are really like that at all so what have I just experienced? Some sort of elaborate psychic message? Was it all in my mind? Indeed, did it happen at all? I am tempted to turn back to see if the street has changed but I decide to go home. I am tired and feel completely drained.

Surprisingly, I slept undisturbed and woke feeling refreshed. As I sit at my table sipping my morning cup of tea, munching toast and marmalade, I find myself thinking about Nancy Derebohn and her anguish which I can now understand. She was brutally murdered by her husband and her body hidden somewhere. That must be why she has shown herself to me. I gaze out of my window at the patch of azure sky I can see above Rodney Street. I know I must go back and see the house as it is today. I make my mind up. I will go this morning after I have done a brief shop for necessities. My fridge is forlornly empty, and I have even run out of staples like bread and soup. On the rare occasion I see my brother who lives in Snowdonia, he keeps telling me I have lost weight. Maybe I have. It is just that sometimes I am just too busy to eat. Yes, I know I should make a point of having at least one good meal a day and I do try.

The bus takes me within walking distance of Freshfield Road, this time in broad daylight with a blue sky and a gleaming sun shining down. No macabre visions this time surely?

The road could not be more different to the one I walked down last night. There are cars lining one side; people are walking; people are talking; it is all bustle. I smile and then when I am within sight of number 92, I stop in my tracks. What do I say to whoever opens the door? I hadn’t thought of that. I can’t tell the whole story; not at first anyway because the occupants will think I’m mad. I think for a few moments and decide on my approach.

When I reach the house, it could not be more different. It is brightly painted with modern double glazing and curtains at the windows. And there is a bell.

I hesitate and then, my mind made up, I press it a couple of times. There is no response, although I think I can detect movement. I stand there undecided. Should I just go? I have turned on my heel when the door suddenly opens and a flustered-looking woman in her early 20s looks at me enquiringly. I clear my throat and say that I am sorry to bother her, but I wonder if I might have ten minutes of her time. When she looks at me blankly, I plough on and say that it is about a woman who used to live at this house by the name of Nancy Derebohn and that she might be able to help solve a mystery.

She frowns as if trying to decide if I am for real or not. She asks me who I am, so I tell her but leaving out my psychic abilities…for now anyway.

She opens the door wider and ushers me into the sitting room which is bright, cheerful with a couple of comfortable armchairs and a sofa. So different from my last visit.

‘I have just put the baby down,’ she says smiling. I fervently hope she means the baby is asleep and not dead. ‘Mornings are always a bit hectic, especially when I’m working. I am Alice Worthington by the way,’ she says holding out her hand. We shake, smiling. ‘Now, how can I help you,’ she says. ‘You mentioned Nancy Derebohn. I know she and her husband used to live here.’ I nod. ‘And then, apparently, one day she just vanished.’

‘I think she was murdered,’ I say, deciding to take the plunge. ‘And I suspect it was her husband who killed her, here in this house.’

She stares at me, a look of horror on her face. ‘Here,’ she whispers, looking around.

Quite possibly in this room,’ I continue sighing. She puts her hand to her mouth and then a perplexed look crosses her face.

‘Can I tell you something,’ she says. I nod. ‘You must promise you won’t laugh though,’ I tell her I won’t and look at her expectantly.

‘I think this house is haunted,’ she says. ‘There are quite often rappings on the wall behind you when there is nobody in the next room and things have disappeared and very often, I can feel as though there is somebody here.’

‘Yes, I can feel it now,’ I say.

‘You can?’ I nod.

‘A few months ago, I friend of mine was here staying the night and she saw a grey lady who she said looked very sad.’

‘I saw her yesterday,’ I say, coming to a decision. ‘What I haven’t told you is that I came here yesterday but neither the house nor indeed the road looks like they do today. I’m still puzzled by it quite honestly.’ She stares at me, her eyes wide.

Then I told her about how I saw Nancy’s murder being enacted in this very room.

‘Oh my God,’ mutters Alice, looking around again.

I put my hand on her shoulder. ‘It’s OK,’ I tell her. ‘You have nothing to be afraid of. Nancy wants justice. That’s why she is haunting this place and that’s why she has appeared to me several times.’

Lucy stares at me. ‘Would you like a coffee?’ I nod and she disappears into the kitchen and I can hear the kettle being put on and mugs being arranged.

When she returns, she hands me a piping hot mug. ‘How do you know all this?’ she says. I explain that I am a psychic investigator and that Nancy first appeared to me at a pub reading not far away.

When I have finished recounting the chain of events that led to me coming here, she leans back in her chair and then suddenly stands up and says she wants to show me something. We walk over to the window and she points to a well-kept lawn outside.

‘Do you see the flowers,’ she says. I look at the lawn and there is a yellow rectangle of buttercups in the centre. ‘They are pretty,’ I say. ‘We never planted them,’ she says. ‘They are always there, whatever the weather. Really strange.’

I ask if we can walk outside and when I look down at the flowers I know, without any doubt, that is where we will find Nancy Derebohn.

I tell Alice and she stares at the buttercups, tears in her eyes. She looks at me. What do we do?’ she asks.

‘We must tell the Police,’ I say getting out my mobile.

Two days later a forensic team with an imaging scanner arrive. Within hours they had established that there was something buried in the garden. Alice Worthington and her family were moved out to a hotel for a week while a tent was erected in the garden. At first, there had been scepticism at Admiral Street Police Station following Naomi’s call. But then, her track record had persuaded Inspector Salisbury that it was worth an initial investigation, especially if it had any chance of closing the file on Nancy Derebohn.

At the end of the week, they issued a statement saying that the remains of Mrs Derebohn had been recovered and that her husband Roy was helping police with their enquiries.

The Liverpool Echo

At Liverpool Crown Court today, the case of missing housewife Nancy Derebohn was finally closed when her husband, Roy Arthur Derebohn, was convicted of her murder and sentenced to a minimum of 25 years jail.

Mrs Derebohn, of Freshfield Road, Wavertree, inexplicably vanished 15 years ago after telling her husband she was going to visit her sister a few streets away, but she never arrived.

Extensive searches of the area failed to produce any clues as to her whereabouts and a fingertip search by Police of nearby Wavertree Park, known locally as ‘The Mystery’ also failed to shine any light on her disappearance.

Her body was discovered buried in the garden of their home on Freshfield Road after police used imaging technology to conduct a search.

The court was told by the prosecution that Derebohn had bludgeoned his wife to death after returning home in a drunken rage and that it was not until the following morning that he had buried her body in the garden.

Trial Judge Rupert Trenholme QC, when sentencing Derebohn, described him as callous and totally devoid of human feelings and that the savagery of his crime was beyond belief.

Detective Inspector Mark Salisbury, in welcoming the sentence, refused to confirm that it was the intervention of a psychic that had led to the discovery.

The link for anyone interested is http://www.saatchiart.com/mikerickett

MY name is Timothy and I’m a tabby cat. I know that because I’ve heard my owner Jessica telling people all about me. I’m not sure what a tabby cat is supposed to be quite honestly, and I don’t really care. My owner tickles me under my chin when she’s telling people, and I purr to show my appreciation.

When I was a kitten, all I cared about really was having fun . . . and food of course. I still enjoy food, especially when my owner passes me tasty bits she doesn’t like under the table. I don’t think she is supposed to do that because her mum found out once and she got told off and I was chased out of the room. She was told she shouldn’t encourage me.

But she still does it when nobody notices me sneaking in the room under the table.

I still like having fun. I can spend hours playing with a ball of wool or a little toy mouse Jessica gave me. I would much prefer chasing a real one but there aren’t any in our house. Anyway, I have lots of fun chasing the toy one around the room. She even gave me a little house to live in. It is still in the corner of the kitchen, and I can look out of its window and Jessica looks back at me laughing.

What I really like though on cold winter nights is curling up in front of the fire and having a good sleep.

Now that I’m a grown-up cat they let me out every day and I really enjoy that. There are so many interesting smells in our garden including one I recognise but don’t like much. It’s the fox that wanders around, usually of a night, but sometimes in the day.

I met him one day in the back garden. He stared at me and for a while I thought he was going to attack me; his face was curled up in a snarl, but I fluffed up my fur, bared my sharp little teeth and hissed at him. He turned and ran off the coward!

I think he has avoided me ever since. Typical of a coward.

I do have a little friend in the garden though. It’s Mr tortoise who slowly makes his way around the garden. I tease him sometimes by putting my paws on his shell, stopping him walking. He usually turns his head and gives me a look as if to say: ‘Give over, will you. I’m hungry.’ He likes hay which Jessica puts out for him every few days.

I really shouldn’t tease him though and Jessica tells me off when she catches me. She scolds me saying: ‘You don’t treat friends like that.’ She is probably right.

I wake up this morning to the sound of laughing and screams of happiness. I walked out of my house and into the sitting room to see Jessica’s dad dragging the most enormous Christmas tree into the room with Jessica and her sister Emily dancing with delight while her mum looked on smiling. I remember the tree they had last year but this one is much bigger. I learned not to go too near it because of things falling off it.

Jessica spots me and picks me up cradling me in her arms. She strokes me under my chin, knowing I really like that. I give her hand a little lick.

‘Look at our huge tree Timmy,’ she says to me, giving me a little squeeze. We are all going to decorate it later. That will be fun, won’t it?’

‘It’s going to be Christmas soon,’ she says and then there will be presents and fun and lots of lovely things to eat. We will have special treats for you too, won’t we Emily? She joins her sister and gives my back a nice stroke. I wonder if that means I will get lots of turkey bits under the table. Hmmm, I will look forward to that.

‘We are all going to sing Christmas carols tonight,’ announces her dad. It’s Carols by Candlelight in church.’ I suppose that means I will be on my own, but I don’t mind. I may go out though the cat flap in the back door if I feel like doing a bit of exploring.

I wake up. I must have dozed off. I remember curling up on a cushion on my favourite armchair after my meal. It’s actually Jessica’s dad’s and I sneak onto it when he isn’t here. I know he complains about my fur, but I think he likes me really.

Anyway, I am all warm in front of the fire and there is the usual hubbub at dinner time which was a bit more so today because they all have to be ready to go out to sing carols, whatever they are. I just leave them to it.

It is later and the house is completely dark and silent. I am in my house in the kitchen and the moon is gleaming brightly through the windows and lighting up the walls as I walk into the sitting room which is lit by lots of twinkling lights on the tree and reflected off the walls. They look really nice, and I notice a gleaming silver orb on the carpet. It must have fallen off. I push it with my paw, and it scuttles off across the room. I chase after it and bat it to the far corner. This is fun.

After I while I get tired of that and decide to go out through the flap on the back door. I quite enjoy the nights even if the street lights only dimly light up the roads. That doesn’t matter because I can see in the dark much better than humans or dogs or even Mr Fox. He had better stay out of my way tonight though.

I am not really afraid of dogs, well not most of them. There are some really vicious ones, and I steer clear of them. In fact, I have a friend a few doors away. His name is Mr Jones, and I go and see him most days. Sometimes he shares his biscuits with me. There is no sign of him tonight though.

I feel adventurous tonight even if it is cold. I just feel like exploring gardens and hedges I haven’t visited before. There will be exciting new smells, new trees to climb and I might even find a mouse or two. I must be careful though not encroach on somebody’s territory. Other cats can be quite nasty if you wander into their garden accidentally and I really don’t want to get into a fight.

I set off down the road outside our house.

The road lights aren’t working so it is very dark which, of course, does not worry me because as I have said I can see extremely well in the dark. There is a very tempting tree across the road which I have not climbed before so I decide it would be fun to do it in the dark and it would also be a good exercise for my claws which need something to scratch from time-to-time and there is nothing better than a tree trunk.

I begin to cross the road and suddenly I am blinded by the headlights of a car which is roaring towards me. I freeze, not knowing which way to go and then, realising I am in great danger, I hurl myself forward. There is a screech of brakes and the car slides to s stop. I run and hide in a hedge just under the tree.

Two car doors open: ‘Have you run him over?’ shouts a woman’s voice anxiously. ‘Don’t think so,’ says a man walking around the car and searching for my dead body. ‘No, I think I must have just missed him.’ They both climb back in the car, and it drives off.

I must be more careful in future. These cars are too fast for me. He just missed me this time. I climb the tree and find a nice thick branch to rest on. My heart is thumping away after all that.

As I lie there it starts snowing, just great big juicy flakes at first that just float down gently. I catch a few of them and let them melt in my mouth but then the flakes get smaller, and the snow gets thicker and starts falling faster. It’s getting colder too.

I shelter under the branches for a while but then when it shows no sign of stopping I climb down and run up the road not looking where I’m going really. I scamper down side roads and stop once or twice when I sense a mouse under a hedge, but he must have heard me coming because when I get there, he has vanished.

I am walking down a road I don’t recognise and coming towards me are three boys. One spots me and shouts to the others: ‘Look, there’s a pussycat, let’s grab him and have some fun.’

They run towards me. I don’t like this. I am afraid their idea of fun is to hurt me. I back up against a wall and put up my hackles, hissing at them. One tries to grab me, and I scratch him. He yelps and shows his hand to them. There is a trickle of blood. Another one aims a kick at me, and I easily sidestep that.

‘Let’s all grab him,’ says one. ‘He can’t scratch us all at the same time.’ They run towards me with their arms outstretched. I dodge between their legs and run as fast as I can. They run after me, but they are no match for me, especially since I can squeeze though fences and under hedges as well as climb trees.

I am on a lawn in a garden. There is a light from the window. The boys spot me and walk through the gate. ‘There he is, let’s grab him.’ They open the gate and walk on to the lawn and as they do so the front door opens, and a man stands there and glowers at them.

‘What do you think you are doing?’ he roars at them. ‘Get off my lawn or I’ll call the police.’

‘We just came to get our cat,’ one says.

‘What cat?’ says the man. They all look around the lawn, but I have sneaked away.

‘You’re all up to no good,’ yells the man. Get lost or else . . .’ He brandishes his phone and the boys leave pulling faces at him as they go.

I have run far away and finally I stop. I want to go home to my nice warm cushion in front of the fire or to my house, but I don’t know where I am. I am lost, cold and wet. The snow has melted into my fur and even though I shake it off, it makes no difference. The snow is coming down even harder than before. I don’t know what to do or where to go.

I keep walking slowly forward hoping that I will recognise something that will help me find my way back and then I turn a corner and see a large building just down the road. A large door is open and a warm, orange, light is shining through. I decide to head for it hoping I can go in. Maybe I can hide before anyone notices me.

I creep in and in front of me are two more doors, this time made of glass which is where the light is streaming from. I am so cold I am trembling. It would be nice to go inside where it will be warmer. Just as I am wondering how I can get in a man emerges from a side door and opens one of the glass doors wide. I slink inside before it closes.

It is very much warmer in here and full of people all sitting in rows. Suddenly, they all start singing ‘Once in Royal David’s City.’ They are so busy singing nobody notices me as I walk down a passageway and stop at the end of the back row where a lady is singing really nicely. She looks like a nice lady, so I walk into the row and rub myself on her ankle and meow pitifully.

She looks down at me and stops singing. ‘Hello puss,’ she says reaching down and cradling me in her arms. ‘You’re cold and soaking you poor thing,’ she says wrapping her scarf around me. I lick her hand and purr as a way of saying thanks.

‘Looks like you have a new friend,’ says the man sitting next to her. ‘The poor thing is freezing and soaking. He would have frozen to death outside,’ she replies. ‘I’ll put him in my bag with scarf wrapped around him. He’ll warm up in no time.’

She has a large shopping bag on the floor which she carefully puts me in. I don’t mind at all. It’s warm and smells nice and then they all start singing again. ‘Hark the Herald Angels Sing.’ It must have something to do with Christmas I think.

I am finally beginning to feel warmer, and the scarf has absorbed a lot of the damp from my fur. I can feel myself feeling sleepy . . .

I have no idea how long I slept. I can suddenly feel myself moving. I peep over the top of the bag the lady is carrying me in and see we are heading for a car. What should I do? I want to go home; I don’t really want to go somewhere else but it’s still snowing hard, and I still have no idea where I am. Maybe the lady will try to find out where I live. Even better, maybe she will give me something nice to eat as well. I settle back down in the shopping bag and hope for the best.

We arrive at a large house, and I am carried in, my head above the shopping bag and my paws resting on the top. They carry me into a room where there is also a nice fire. The lady carefully places me down in front of it, stroking me as she does so. I give her hand a good lick as a thank you.

‘There puss, I’ll see what I can find for you to eat.’ She goes away and I curl up in front of the fire.

She returns with a bowl, and I can smell fish, sardines I think. She puts it down with a saucer of milk and I gobble it them both up gratefully.

When I finish she sees the tag around my neck and reads it. ‘So, your name is Timothy I see. Hello Timothy, what are doing out in weather like this? Your owner must be really worried about you.’ She reads the tag again. ‘Ah, I see there’s a phone number. I’ll ring it in the morning. It’s a bit too late tonight.’

She goes away and returns with a soft cushion. She gently places me on top of it. ‘There Timothy, that will be your bed.’ She wags a finger at me: ‘There will be no more adventures outside for you tonight. You are going to stay here in the warmth and tomorrow we will try and find your owner.’ She strokes me and I purr. ‘I would love to have a puss like you. I bet your owner is missing you terribly.’

She gives me a final stroke and walks away, switching the light off before closing the door. I settle down on my cushion. I am safe, I am warm, I have had a good feed. I curl up on my cushion and sink into a deep sleep.

I am awake quite early the next morning and although the curtains are still drawn that doesn’t stop me exploring the room I am in. There is a very tempting armchair in the corner with three dolls on it. I am curious. What are they doing here? I jump up on to it and have a little play with them. They appear to be made of rags, and they all have smiley faces. One is wearing a Father Christmas hat. I pull it off and toss it about. The dolls don’t seem to mind.

Not long after the door opens and the lady walks in and draws the curtains. She spots me on the armchair and rushes over to rescue her dolls. ‘You naughty cat Timothy. These are my dolls. I make them for people, especially at Christmas.’ She seizes the hat. ‘Look at that, you have torn it. I have to make another one now.’

She carries me back to the cushion and reaches for a bottle of milk she had brought with her. She pours some into the saucer. ‘That should keep you busy, and I have another tin of sardines you can have soon. I am going to ring your owner now and tell them that I have found you.’

I am pleased to hear that. It’s nice here but I would still rather be at home.

It isn’t long before Jessica and her mum arrive. I am overjoyed to see her. She picks me up and gives me a big hug. I lick her face. She wags a finger and scolds me: ‘You’re a very naughty puss wandering off like that,’ and then strokes me.

‘Where did you find him?’ Jessica’s mum asks the lady.

‘Well, he found me really,’ she answers, laughing. We were at All Hallows Church for Carols by Candlelight, and I felt something wet rubbing itself against my leg. I looked down and there he was, poor thing. He was soaking and looked really sorry for himself, so I wrapped my scarf around him and put him in my shopping bag. He fell asleep until we got home.’

Jessica and her mum exchange looks. ‘We were at Carols by Candlelight too. How strange is that?’ says Jessica’s mum.

‘He must have been looking for us,’ declares Jessica. The two women exchange knowing smiles.

‘Thank you for looking after him,’ say Jessica to the lady.

‘We must be going,’ says Jessica’s mum. ‘We have a lot to do with it being Christmas Eve.’ They wish each other a Happy Christmas and we set off home.

I am back in my house after another meal. Jessica isn’t to know that I have already been fed. Naturally, I am not about to complain. I tucked of course!

Everyone is busy. Jessica and Emily are in their rooms wrapping presents and her mum and dad have gone off shopping. When I wondered into the kitchen earlier I noticed a large turkey on the table. I eyed it up and was tempted to jump up onto the table just to have a look, nothing more. Honest!

I didn’t anyway, mostly because I could hear Jessica and Emily coming downstairs. They came into the kitchen wearing Father Christmas hats. Jessica looked at me and then at the turkey. ‘I think we had better put this in the fridge just in case Timothy gets any ideas,’ she says grinning.

As if I would!

When their mum and dad get back the house descends into chaos. There is shopping everywhere and then the cleaning and tidying up begins. I don’t like the vacuum cleaner, and I stay clear of it because it makes my fur stand up. I decide to go out into the garden to get out of the way.