Copyright © 2025 Mike Rickett

All rights reserved.

1968

I last ran into Montague Stephens almost a year ago. We bumped into each other in London after a Mozart concert at St Martin-in-the Fields. I was idly standing around clutching a glass of mediocre wine afterwards when he sidled up alongside me. I introduced myself. He looked at me and murmured my name Michael Thorne thoughtfully, his head to one side. I spared him the torture of attempting to recall where he had heard or seen it and told him that I used to be a reporter which is where he no doubt saw my by-line. He nodded, obviously relieved and we enjoyed a really pleasant chat about the relative merits of Mozart and Faure, the latter being my favourite composer.

I was working in London at the time at a PR consultancy in Red Lion Street and he was a history lecturer at the London School of Economics. After the concert we would meet up occasionally for a few drinks and a chat, usually somewhere in Holborn which is where we both lived, until a new job beckoned, and I found myself once again back in Liverpool.

That was six months ago when I rented a really spacious apartment in an area which the newspapers termed ‘Leafy Allerton’ in that jocular way they have of attaching labels to everything.

It is, however, undeniably a ‘leafy’ area and just down the road, nestling in a crossroads, is a historic church built by the 19th century shipowner and merchant John Bibby. It was apparently built at the-then enormous cost of £25,000 as a memorial to his wife whose catafalque lies behind the altar.

I love buildings that have a ‘history’ and this one is a prize example, for quite apart from the founder’s reason for building it in 1872, the church is full of remarkable art in the form of fabulous Arts and Crafts stained glass windows, largely the work of Sir Edward Burne-Jones and Williiam Morris, the founder of the pre-Raphaelite movement.

Anyway, I started going there of a Sunday morning to enjoy Matins and the choir’s singing of the Venite and the Te Deum and Benedicite or the Benedictus or Jubilate Deo. I was a chorister myself as a boy, so I appreciate a good choir.

Anyway, last Sunday I was somewhat surprised to spot Montague in a side aisle before the service staring fixedly at a statue in the south transept. I had no idea he had left London, so I strolled up and gave him a dig in the ribs. ‘You sly dog,’ I said smiling. ‘Why didn’t you get in touch? I had no idea you were in Liverpool.’

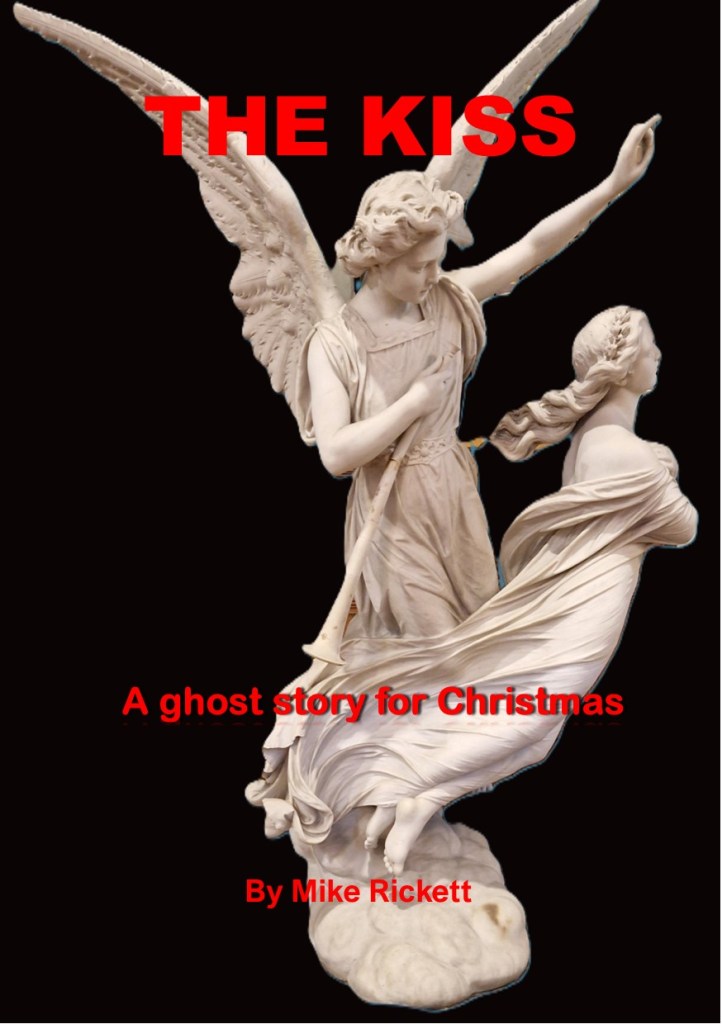

He stares at me vacantly, his eyes glassy until he suddenly appears to realise I am there. ‘Sorry Michael,’ he mutters, ‘I was admiring that sculpture over there.’ He points at what looks like a marble group of figures. I walk over and read the caption, An Angel Carrying a Soul to Heaven. It was carved by the Italian artist Fabiani and is a replica of the one in Genoa.

It must have cost the founder Mr Bibby a small fortune.

‘Magnificent isn’t she?’ he breathes, standing next to me. ‘I can’t take my eyes off her. The church authorities apparently call her ‘Flossie,’ can you imagine that? Disgraceful and insulting,’ he declares indignantly, looking around hoping somebody was within earshot. Nobody is.

He moves a short distance away and summons me to join him. We have our backs to the statue, and he is pointing to a pew just two rows from the front and at the end next to the central aisle.

He lowers his voice to a whisper. ‘I was sitting there last Sunday morning,’ he says sibilantly. ‘The choir had just started singing the Te Deum, do you know it?’ I nod in the affirmative.

‘Well, as you know, when it gets to part where the angels sing God’s praises, I felt a kiss on my cheek. I jumped and looked around but there was nobody there.’

‘You must have imagined it,’ I say to him. ‘It might have been a gust of wind from the Bibby side door over there.’ I point to the door by the vestry.

He shakes his head vehemently. ‘I know what lips feel like. And it was definitely a kiss.’ He stares at me fixedly. ‘It was her,’ he says nodding in the direction of the statue.

I burst out laughing. ‘Don’t be silly Montague. The Angel is a marble statue. They don’t usually suddenly come to life and start kissing people.’

‘I know what I felt,’ he says abruptly and marches off to the door. I turn and stare at ‘Flossie.’ She is certainly beautiful but definitely immovable. I shrug, thinking that poor Montague must be losing it.

It is almost a month later when I next see him. It is a Saturday, mid-December and I am on bustling Allerton Road, full of people with their eyes firmly focussed on the last few shopping days before Christmas. I had just been to the fishmongers for my weekly treat of Manx kippers when I spot him trudging along outside, his head bowed, the very picture of melancholy.

I catch up with him. ‘Montague,’ I call. He stops and turns, and I am disturbed at the change in him. His face is a pasty white and there are yellowish bags under his eyes.

I suggest we go for a coffee. He reluctantly agrees. When we are seated I stare at him. ‘What on Earth has happened to you? You look dreadful. Are you ill?

He smiles grimly. ‘I suppose you could say that.’ He takes a long gulp at his coffee and studies the people around us, muttering: ‘She will be here somewhere. You can’t always tell but she will be watching me. She always is.’

I look around. The café is quite full; there are people in ones and twos, all doing something; chatting, reading, or simply looking at the passing scene outside.

‘Nobody is taking the slightest bit of notice of us,’ I say, hoping to reassure him. Who do you think is watching you; who is she?’

He glares at me. ‘Who do you think? That bloody statue.’ He sighs and slumps in his chair. ‘That first night after I studied her in church. I woke at midnight. I felt something was wrong. I sat up in my bed. I always have the curtains and window slightly open. It was a full moon and there was a shaft of light shining in my room and there in the corner there she was, staring at me. There was something about her eyes. She wanted me to look at her, but I knew that if I did I would be lost. Then she began getting closer, her wings outstretched. I was terrified. I ran out of the flat on to the street in my pyjamas. One or two people walked past even at that time and stared at me curiously.’ His brow is furrowed as he gives me a pleading look.

‘You know, I think she wants me to join her,’ he whispers.

I am about to make a joke of it by saying she might be doing him a favour by taking him to Heaven, but I don’t. Instead, I say gently: ‘Are you sure you aren’t imagining all this? You might have been overdoing things at the faculty lately. I know there’s a lot of pressure to get Firsts these days. Maybe you should get medical help. Go and see your GP. I’m sure they will suggest something,’ I end a little vaguely.

He reaches into an inside pocket and produces a large, pure white feather. He places it on the table. ‘That was on the floor in the morning,’ he says. ‘Do you still think I imagined it?

I am lost for words. I stare at it. ‘Monty, I assume you mean Flossie by She, don’t you?’

‘Don’t call her that,’ he snaps. ‘She doesn’t like it.’

I frown. ‘Whatever you want to call her, she is a marble sculpture.

Nothing more. She can’t suddenly come to life. It is just impossible.’ I pick up the feather and hold it up. ‘And this could quite simply have blown in through the window. It looks like a seagull feather to me.’

He snatches it back and scowls, backing away. ‘You don’t believe me, do you, but you will, just wait and see.’ And with that he slinks off.

I am in a quandary. I am worried about him. I find his story difficult to believe and the following Sunday morning I stare at the statue. It is, without a doubt a beautiful piece of work. I wonder why they called her ‘Flossie.’ It seems completely incongruous for something so beautiful. As I stare, her face turns towards me, and she smiles.

I shake my head. I must have been dreaming. I look again and she is unchanged, her finger pointing to Heaven for the departing soul.

After the service I seek out the vicar, the Rev Maurice Bartlett. We are good friends. He was appointed two years ago and we hit it off almost immediately. He prepared me for Confirmation as well as marrying me to the wife I later divorced. He is an intelligent and likeable man, and as a former Guards officer, is well versed in the ways of the world.

We both enjoyed a lively debate, and I would rather impudently introduce topics like ‘What is God?’ usually accompanied by a whisky or two.

Anyway, I decide to ask if we could have a chat and later, in the early evening, I call around to the vicarage.

Once we have dispensed with the preliminaries, I tell him about Montague and his fantasy which is what I have decided to call it.

After I have finished he is silent for a while. Finally, he frowns. ‘He isn’t the only one to think there is something about ‘Flossie.’ One or two people have said they have had disturbing dreams about her, to the point in one or two cases, where they have even stopped coming.’

I am astonished and ask him if he is serious because Maurice can sometimes be a bit of leg-puller. He assures me he is.

‘There is something else too,’ he continues. One or two people who have been in the church of a night when just one or two lights are on, and they say they have felt a presence there and usually leave as soon as they can.’

‘Have you ever felt that?’ I ask. ‘You must have been there many times on your own.’ He grimaces and says he honestly hasn’t. ‘Maybe the presence is scared of me,’ he says grinning.

‘Maybe it’s Fanny Bibby getting out of her catafalque,’ I respond. ‘Perhaps she and Flossie get together for a bit of a chinwag when nobody is around. We both laugh at that thought.

He is looking thoughtful. ‘There is something else too that has been reported to me. A strange light has sometimes been seen in the North Chancel window. No other light have been on in the church, just in that window.’

He studies me. ‘You probably don’t understand the significance of that. That window was installed by Burne Jones in 1881. It depicts angels and is a memorial to John Bibby’s children.’

He looks at me questioningly. ‘Angels again you see. If you are looking for a reason, maybe that’s it.’

‘So, it comes back to “Flossie again.’” I say. He nods.

I sigh. ‘So, you are saying that it is distinctly possible that Montague isn’t imagining all this. Is that right?’

‘Oh well, I wouldn’t go that far,’ he says hurriedly. ‘It is entirely possible he has some kind of mental disorder which has magnified the stories about ‘Flossie’ he may have heard. He really needs to see a doctor.’

It is exactly the same conclusion I had come to, and I told him so. I stare at him quizzingly. ‘Do you actually believe all the stuff you’ve told me?

‘Let me refer you to the Bible,’ he says. ‘In my Father’s house are many mansions: if it were not so, I would have told you. I go to prepare a place for you. And if I go and prepare a place for you, I will come again and receive you unto myself; that where I am, there ye may be also. And whither I go ye know, and the way ye know.’

‘Is that a “yes” or a “no”?’ I ask.

‘I’ll let you decide,’ is his response.

On my way back to my flat, my thoughts return to that odd dream, if that’s what it was, I had in the church. It can only have lasted for perhaps a few seconds and then the statue was back to normal. I shiver.

Back in my flat I notice there is a message on my phone machine. It is from Montague. He sounds agitated. I press callback but it just rings out. I decide to go around and find out what the problem is and why he isn’t answering his phone.

When I get there he is sitting on his step, his head in his hands. ‘She won’t leave me alone,’ is all he says pleadingly, nodding inside. I assume he means ‘Flossie.’

‘What do you mean? I ask.

‘She is in my room all night. I am too scared to close my eyes. I don’t think I would wake up.’ I shake my head and sigh. I tell him I will go and look around. I’m not sure what I expect to find.

There is nothing unusual in any of the rooms. I join him on the step and tell him that everything is entirely normal and then an idea comes to me. ‘Why don’t you go away for a few days; a week perhaps? Do you have anyone you could stay with for a while? You don’t have to tell them exactly why; just tell them that you urgently need a break.’

‘There’s my sister Polly in London,’ he says slowly. I tell him to ring her straight away and if she agrees I will run him to the station. He disappears inside and returns. He asks me to go with him while he packs a bag. I takes him just ten minutes.

I drop him off at Lime Street Station. His demeanour has completely changed. He was smiling broadly when he climbs out of the car, and I congratulate myself on a problem well solved.

The following Sunday I go to church. It is Matins as usual but this week with the addition of the Eucharist following. While the choir are singing I stare wonderingly at the statue. I was about halfway down the Nave but even at this distance I can tell there is that indefinable something about her. I know this sounds insane, but I can almost feel her studying me.

At the end of the service, I seek out Maurice and update him on Montague. He agrees that it was exactly the right course of action.

That night I watch the BBC’s excellent annual ghost offerings. It is always one of M R James’ s creepy ghost stories. This year it is The Stalls of Barchester. A scholar, Dr Black is engaged in cataloguing the collection of the library of Barchester Cathedral. He is finding the work heavy going. However, the librarian and Dr Black begin reading the diary of Dr Haynes, an ambitious cleric who finds his promotion to Archdeacon blocked by a geriatric incumbent. The impatient Haynes, played by Robert Hardy, conspires to hasten the Archdeacon’s death and is duly appointed Archdeacon. However, his diary reveals that once in post Haynes becomes increasingly disturbed and is plagued by unnerving events, including a phantom cat, and carvings coming alive in the cathedral stalls.

I’m not sure whether it was that or ‘Flossie’s’ alleged hauntings, but my night was extremely disturbed. I awoke at 2.00am, or I thought I did but I can’t be sure. I may have been dreaming. It was a sound in my room I think, a strange rustling. I glanced at my window which I always leave slightly open, thinking that perhaps a bird may be in the gutters. But the sound wasn’t coming from there; it appeared to be nearer the door.

My room is never completely dark, even though my curtains are drawn. A lamppost outside casts an orange glow which permeates through my curtains. The orange glow is brightest on the door, almost opposite my bed. As I stare at it, I can see the door handle slowly moving. I gaze in horror as it stops, and the door gradually begins to

open. ‘Who’s there?’ I shout. I follow it up with ‘I’m ringing the police.’ I stand by the side of my bed.

The door is open wide now. Beyond is the hall in a blackness but as I stare, I can see a shape or shapes which are moving or writhing. I scream and fall onto the bed.

The sun is shining through my curtains. I am lying on my bed. Why am I on the bed and not in it? And then I remember the nightmare. Was it a nightmare? I’m not sure. It is all a bit fuzzy. I recall it had something to do with the door. I glance at it, but it is firmly shut.

I have a feeling of unease or dread, and I don’t know why. I search every room in the flat. I’m not sure what I expect to find but everything is as it should be.

I go to work which is taken up with the demands of a client in the form of the Plessey company on Edge Lane. The nightmare fades as nightmares so often do and the following nights are undisturbed which convinces me that it was all in my imagination.

The following Friday there is a message on my phone informing me that Montague is back home in his flat after a ‘really enjoyable week’ and would I fancy a pint or two a little later? I ring him later and we agree to meet up in the Rose of Mossley pub on Rose Lane.

I almost fail to recognise him when I spot him leaning on the bar. He is all smiles, transformed from the introspective, gloomy man who had set off to London. ‘You know, I think you may have been right,’ he informs me when we are sitting down. ‘I really do think it may have all been in my mind.’ I have to stop myself telling him about the ‘incident’ in church when I imagined ‘Flossie’ smiling at me.

He tells me he is moving back to college in London next week and I am welcome to visit whenever I want. I thank him.

As we part I ask him if he is likely to be paying All Hallows a final visit on Sunday. He stops and he stares at me strangely, an odd expression I cannot quite define before saying quietly: ‘I think not.’ And with that we part.

The following Monday my phone rings as I am about to go to work when my doorbell rings. Outside are two men who stare at me grimly.

‘Mr Thorne?’ It’s more of statement than a question. He produces a warrant card and introduces himself as Inspector Dean and his colleague as sergeant Finney. He asks if they could come in ‘for a chat concerning Mr Montague Stephens.’ I lead them into the kitchen and look at them expectantly.

‘We understand you are a friend of Mr Stephens,’ the inspector says. I nod. ‘When did you last see him?’ he then asks.

I briefly recount our conversation the previous Friday and tell them that he was intending to return to his college today. I raise an eyebrow expectantly and ask if anything is wrong.

They exchange glances. ‘I’m afraid we have some rather bad news,’ says the inspector. ‘Mr Stephens was found dead earlier this morning.’

I am stunned. ‘He was fine on Friday and in perfect health. What happened?’

‘We aren’t sure. As yet we haven’t been able to establish a cause of death. There is no sign of a disturbance despite a neighbour hearing shouting and a cry for help which is why he contacted us.

The pathologist was unable to throw any light at the scene. We will know more after a postmortem. Our immediate task is to notify next of kin. Would you be able to help with that?’

I tell him that he had just returned from visiting his sister in London and that the London School of Economics would undoubtedly have details. He nods and they turn to go. As they are about to walk out, he turns: ‘There was just one thing. He had a very odd expression on his face; both his eyes and his mouth where wide open as though something had deeply shocked him. I’ve never seen anything quite like it.’ He shakes his head mournfully and they leave.

It was a few days later that I learned that the postmortem decided he died from cardiac Arrhythmia or seizure, but they were unable to say what caused it.

I am disturbed. What could have happened to him? Inevitably, my thoughts turn to ‘Flossie.’ Could she have had something to do with it? And just as speedily, I dismiss it. That is just too ridiculous for words. It was probably a heart attack. I know of people who have literally dropped dead on the spot because of that. What is the betting that is what the PM will find. All the same, I feel unsettled for the rest of the day and decide to call on Maurice at the vicarage later.

He agrees with my diagnosis when I outline what the police have told me. ‘He was obviously a very disturbed man,’ he says quietly. ‘I shall pray for him.’ He then treats me to a calculating look. ‘You mustn’t let all this get to you. You did what you could to help him. You have nothing to reproach yourself for.’

The following day, a Saturday, is spent in Liverpool’s Central Library researching the science behind wire-free communications for the Plessey company, something that promises to revolutionise life in the future.

That evening is very disturbed again. I can’t relax and I have no idea why. I have the feeling I am not alone which is crazy but all the same I keep imagining I see movement out of the corner of my eye but when I turn to look there is nothing there. Am I imagining it? All this business with Montague has really unsettled me. I decide on an early night. Perhaps things will feel better in the morning.

I awake suddenly. I’m not sure why; was it a noise or something else? I’m not sure. I do know it is very cold and a shaft of moonlight shines coldly through the gap in my curtains lighting up something moving on the opposite wall. I sit up and stare. At first it looks like an image of something grotesque, a writhing mass of flesh which gradually coalesces into a pair of eyes which protrude from the wall and are slowly surrounded by a pair of wings and then an upper female body.

The eyes bore into me and the entire apparition begins to slowly move towards me until it reaches the end of my bed. I shrink back and try to scream but I can’t because my throat is so constricted all that emerges is a dry croak. I lurch sideways and fall onto the floor, banging my head on something hard.

I awake on the floor. I am cold, very cold. Daylight is streaming through the window. What am I doing on the floor? I am trembling and stand, reaching for my dressing gown. It is then I remember the nightmare. I must have fallen on the floor when I was writhing in bed.

But was it really a nightmare?

It must have been. I stare at the wall. All nightmares are vivid at first and then become a little fuzzy. I close my eyes, and I can still see the apparition. It didn’t feel like a nightmare. It was just so real. I shudder.

I decide to go to church after breakfast. The walk will do me good anyway and, hopefully, the uneasy feeling that has descended on me will dissipate.

I choose a pew on the opposite side of the church from ‘Flossie,’ and I am also behind a pillar so that I do not have line of sight of her. I’m not sure why. I just feel I want to distance myself from the statue. I am also at the end of the pew next to a side aisle.

The uneasy feeling has failed to dissipate; if anything, it becomes stronger as the service proceeds.

The choir start singing the Te Deum and as they sing: ‘To thee all Angels cry aloud: the Heavens, and all the Powers therein. To thee Cherubin and Seraphin: continually do cry.’

I am staring at the pew in front of me and suddenly fingers begin slowly crawling their way over the top. At first I assume there must be a child sitting there, but there is nobody there. I stare at them in horror; they are a deathly white, slightly green as though rotting.

It is then I feel a kiss on my cheek . . .

About the author

Mike Rickett is a member of All Hallows Choir. He is an artist and a writer. He was previously a daily newspaper journalist and at one time was head of public relations for National Girobank and PR Executive for the Plessey Company.

Leave a comment